Guest Blog: Crewing Kelsey at UTMB 2024

Written by Lori Dithurbide

The crew at the finish! L-R: Stef, Noel, Adam, Kelsey, Jane, Kaylee, Lori

My definition of endurance sport is a 5-hour round of golf. So, when Kelsey Hogan, an ultra-marathon runner and new graduate student, asked if I would ever consider crewing for her, I’ll admit I chuckled. When she insisted she was serious, all I could think of was the idea of helping to motivate someone to keep running past 50, 100, or even 150kms may not be one of my strengths considering I have little desire to run further than 2km on a good day. Little did I know that two years later I would find myself chasing Kelsey around Mont Blanc, along with the rest of her crew, executing carefully planned aid station stops akin to Formula 1 pit stops.

Kelsey began her graduate degree under my supervision in the Fall of 2021. She came with an infectious and enthusiastic desire to learn and a unique research interest: the mental aspects and performance of ultra-marathoners. While not quite in my area of interest, she had enough passion in the topic for me to know that this was going to be an exciting learning opportunity for the both of us. And boy did I learn! I may have asked Kelsey as many questions about ultra-marathons and her races as she asked me about mental performance consulting and research. While I have yet to be personally motivated to hit the mountains to run for extreme distances (I don’t anticipate this EVER happening), I was sucked into the ultra-marathon world, as a fan, quickly.

Fast-forward to early 2024, Kelsey having successfully completed her MScKINE months prior, when we were catching up over a Zoom meeting. I was telling Kelsey about my potential sabbatical summer travel in Europe, and she quietly asked again, if I would consider crewing for her – this time for a specific race – at the Ultra Trail du Mont Blanc. This time, I accepted.

In her relatively young career as an ultra-marathon runner, Kelsey has experienced quite a bit of success – winning a handful of races, course records, and top 10 finishes in challenging international races – which has led to her becoming a professional and elite runner (see @kelseypamela on Instagram). While her physical abilities and physiological make-up contribute immensely to her success, Kelsey’s positive attitude and sheer joy on the trails seems to set her apart from the rest. This is her superpower. In preparation for an earlier race in the season, Kelsey and I were discussing the perceived transition from running for the joy of it to racing professionally. That type of transition can be tricky in any sport and comes with different pressures to perform. Our strategy to help manage that pressure became embracing her superpower: her sheer genuine joy of trail running.

The weeks leading up to the race included watching race documentaries to familiarize myself with the course and the area, watching clips of top runners going through aid stations faster than race cars going through the pit lane, and asking a whole lot of questions. The questions were for both Kelsey and my benefit. For her, to really reflect on how she wanted to be supported by her entire crew and her needs throughout the race, and for me, to feel at least a little bit like I knew what I was doing. Kelsey’s crew also included her partner Adam (also an ultra-runner), her parents Jane and Noel who have crewed for her at multiple races, Stef – a friend who crewed Kelsey at UTMB in 2023, and Kaylee – a trail running friend and also a crew rookie like me. We would be the team who would board the crew busses chasing Kelsey across three countries.

Kelsey had run UTMB in 2023 after having qualified through a race she ran earlier that year. Her result in the qualifying race (5th at Ultra Trail Snowdonia) earned her a spot at UTMB for both 2023 and 2024. While last year’s race was a late addition to the schedule and would serve as sort of a reconnaissance mission, this year it would be on her calendar from the beginning, following up two competitive World Trail Majors races earlier in the race season (MIUT 115K and Quebec Mega Trail 100M). I had asked Kelsey what her goal was for this year. The thing with ultramarathons is that because they are so long – in distance and time – really anything can happen. Consequently, setting specific goals can be challenging. Kelsey set a series of performance goals in relation to last years’ time and competitors’ times, with her primary goal to be faster than 2023 (34.5 hours).

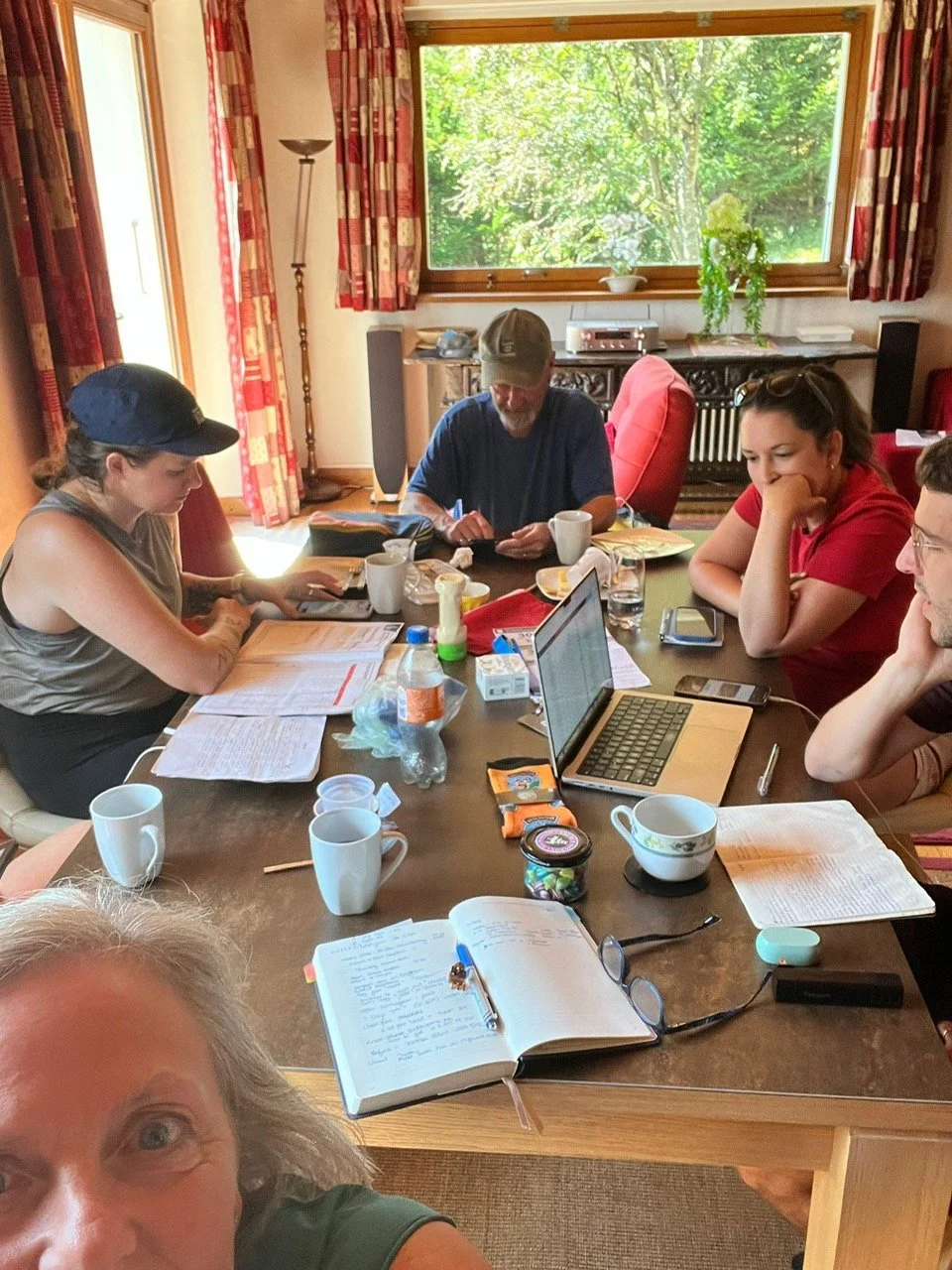

Team meetings to go over the crew plan/race details.

Crew planning and studying maps/bus routes.

When the crew arrived in Chamonix, France three days before the start of the race, we had a pretty good plan laid out to be prepared for start time: crew meetings to go over details, aid station practice runs, watching the finishes of other races, consuming delicious French food, and exploring the surrounding areas. Kelsey had done a really great job in reflecting on her own race needs, starting from the days leading up to the race (e.g., time and space to pack her vest, crew bag, and rest) to the days after (e.g., rest and refueling). We were given direction on what to say (and not to say) at different points in the race, how and when she wanted to be pushed, and what signs to look out for if we had concern for her wellbeing during the race.

At UTMB, only one crew person is permitted in the each of five different assisted aid stations along the race route (there are 10 other unassisted aid stations where runners cannot be assisted by crew). Kelsey assigned each aid station to one of us according to each of our strengths. Her partner Adam would not be manning the aid stations, but instead would be running alongside of her leading into and out of each station. I was assigned the aid station at the 146km mark in Trient, Switzerland, and where Kelsey struggled in last year’s race. In the attempt to make sure I met her needs at this point in the race, we had some in depth conversations about what “struggling” really looked like when she had not slept for hours, had already run the equivalent of over three marathons, and having already climbed over 8000m in the Alps… with 30km and almost 2000m of that in climbs left to go. She was clear that she wanted to be pushed, to not let her stall or delay in the aid station, and to be directed to leave the runners behind her in the dust. She was sure of my abilities to be firm with her, give her confidence, and to pull out the competitiveness in her to transition from running to racing. I was a little less sure of myself and more so worried I would be too concerned that she was in serious pain.

Race Day

UTMB has a start time of 6pm on a Friday evening. Lining up for the runners begins a couple hours pre-race since there are almost 3000 runners, however, because Kelsey is considered an elite category runner, she had her own corral at the start of the line. This meant we could mosey down to the start line between 5-5:30pm. I cannot accurately describe the atmosphere at that start line (and even the 1km radius around the start line) in the small alpine town of Chamonix. The build-up background music, anticipation, the fear, the excitement, the emotions… we were all in tears at some point. And when she was ready to say her goodbyes, Kelsey decided it was time to find her spot at the start line. I was determined to not cry at the start line, so I put my game-face on, gave her a strong hug, and reminded her of her superpower.

Cue crew assuming positions. Her partner Adam was going straight to the train station to make sure he met her at the 13km mark in Les Houches. The rest of us would position ourselves further down from the start line, along the street in Chamonix, with an easy exit to the way towards the crew bus station. We managed to catch a video of Kelsey sprinting by us and then our own race began.

Our first stop was the first crewed aid station in Les Contamines at the 31km mark. Our planning paid off (thanks to Stef) and we made the first crew bus to the station. And despite the rush hour and race traffic up and over the first climb of the course, we arrived at the aid station to join the thousands of running fans with extra time. To say this aid station was chaos would be an understatement. Because there has not been much time and space to spread out the runners at this point in the race, the number of runners coming through and their crew trying to access them was a sight to behold. We had heard from Adam that Kelsey was doing ok through Les Houches but seemed a bit hesitant. This aid station was assigned to Jane, Kelsey’s mom, who is a bundle of positive energy that would help Kelsey as she moved into the darkness and mountains of the first (and hopefully only) night of the race. The transition of this aid station was so fast (Kelsey arrived a tad earlier than expected) that only two of us were positioned at the exit shoot of the station and saw her leave!

And so began her 50km trek in the dark, from France into Italy, climbing over 3000m to the next crewed aid station in Courmayeur. The crew took the bus back to Chamonix, where half went back to the chalet to catch a bit of sleep, and myself and two other crew members, Stef and Kaylee, got on another bus to travel through the Mont-Blanc tunnel to Courmayeur to ensure we had ample time for Kelsey’s arrival as traffic issues are not uncommon. Once we arrived in Courmayeur, we set up camp on the sport centre floor and got as much rest (and a bit of sleep) as we could before the rest of the crew members arrived a couple of hours later. We could track Kelsey’s progress through the night by using the event website and live tracking. We could tell that she was doing ok through the night, matching for the most part her times from last year, but not seemingly taking advantage of some of the flat and descending parts. We knew she would be patient through the first half of the race, what we did not know at the time was patience was forced upon her by some stomach and fueling challenges.

As one can imagine, fueling is one of the most important factors during an ultramarathon since a runner can burn around 16,000-18,000 calories over the course of the 170km+ race. That’s a lot of food to consume, while running up and down mountains. So, it’s no surprise that digestive issues are not only common but often expected. Add those nervous butterflies in your stomach to the equation and it can get tricky real fast. Unfortunately, Kelsey was having trouble keeping food down, and found herself throwing up throughout the night, unable to really push her pace in the first half of the race.

Despite the challenges, Kelsey entered the Courmayeur aid station shortly after 6:30am in 352nd place overall, an hour faster and over 100 places ahead of last year’s race. The Courmayeur aid station is the largest and often is where runners intend to spend the most time considering it’s at about the half-way point of the race following the first night. It’s also known as the aid station “where people go to die” with one of the highest rates of race withdrawals. Stef was assigned this aid station for Kelsey. With their race knowledge and direct instructions, the goal was to get Kelsey in and out as quickly as possible and make up some ground. Because the course and weather had been dry, there was no need to make any wardrobe or shoe changes, and it was mission accomplished – Kelsey exited the aid station in 8 minutes and passed a whopping 72 runners on her way out! The rest of her crew waited at the exit of the aid station where she ran past us giving a couple of “wohoo”s and high-fives, and she was off again, now with the sun rising over the mountain tops in the warming daylight.

The crew decided to split again at this point. Kelsey’s parents and I were headed farther into the Italian Alps to meet Kelsey on course at the 100km point (Arnouvaz) to cheer her on, while Adam, Stef and Kaylee were making their way back to homebase Chamonix to grab another bus to the Swiss side of the course to meet Kelsey at the 116km mark (La Fouly). One of the intricacies of crewing is navigating the routes to aid stations. The runners typically run through/over/down mountains while main roads for crew vehicles travel around (i.e., the scenic route) the mountains. While there were only 16km between our two crew destinations for the runners, the difference in crew bus routes was a few hours. We would all regroup at the 130km mark, the next crewed aid station at Champex-Lac, Switzerland.

Noel, Jane and I arrived high in the Italian Alps after an interesting bus ride/climb at a campground and café where we would wait to cheer on Kelsey at the bottom of a very steep climb in Arnouvaz. We had time to grab a hot beverage and a snack before we started staring up the side of the mountain to see if we could spot Kelsey on her way down to the checkpoint. The unassisted aid stations are staffed with volunteers, medical personnel, and variety of food and drink for the racers. Although we were not permitted to provide any direct help, we could cheer her on which can offer a big morale boost. The live tracking site is not the most accurate, but it did provide us with some decent estimations on when the runners are approaching the next checkpoint with estimated arrival times that switched to the status of “imminent arrival”. I can safely say that I have developed a serious dislike for the word “imminent” after this race. Imminent meant anywhere from “arriving now!” to “waiting another 20 minutes wondering where the heck your runner is”.

As soon as Kelsey’s status into Arnouvaz switched to “imminent”, I took a shot and called out our secret crew team call: a very loud and crow-like “ca-caw”! Much to our excitement, a very enthusiastic “ca-caw” reply came from the forest before us and about 10 seconds later Kelsey sprang from the forest into view, running down the last little descent into the checkpoint. We cheered her into the tent and met her at its exit where she told us her stomach was starting to settle and she was getting some energy back. After she gave some fueling requests for the next leg, we sent her off on her way up one of the steepest climbs – almost 800m in 5km. The race was on.

Kelsey’s parents and I made our way back to Chamonix, and then onto the next bus to meet Adam, Stef and Kaylee (and Kelsey) in Champex-Lac, Switzerland. The ensuing bus rides up and down those mountains were interesting! Kelsey was making really good time throughout the morning so we did not have time to really explore the area once we arrived. In fact, Kelsey was gaining so much ground that she arrived at the aid station when the live tracking said she still had about 10 minutes left to arrive. The entry to this aid area is a climb where most runners were gingerly shuffling up towards the entry to the tent, and then shuffling their way out. Kelsey came in jogging and energized to meet Kaylee inside, and left dancing and running out of the tent. She was now over 2.5 hours and 170 places ahead of last year at this point in the race. Next stop, Trient at the 146km point and my crew station.

Lori crewing Kelsey at Trient aid station.

Trient is this little town on top of a hill with a pink church. This particular station is situated towards the back of the village so the racers run through little bits of the town prior to arriving to the tent. When the crew arrived in Trient, now traveling together for the remainder of the race, we set up camp on a grassy spot next to the street at the entry of the tent. We got the crew pack ready, and I reviewed my notes (multiple times) as if I was studying for an exam. I was nervous. Her pace on the tracker was great, so we had an idea she was feeling good, but we are now approaching the 23 to 24-hour mark of the race. Other than a pre-race nap Friday afternoon, Kelsey really had not slept in about 32 hours. If you are thinking that any normal human being would be expected to be loopy in this situation, without the running across the Alps, you would be correct. Hallucinations are not uncommon for runners in ultra-marathons. This phenomenon always intrigued me when Kelsey first described her races to me. Kelsey typically experiences some hallucinations towards the end of races, and luckily for her, they are not usually scary. Think rocks or tree stumps on the side of the trail coming to life as woodland animals.

I made my way into the aid-station and laid out the equipment and food that we may need: replacement water bottles, replacement gels and snacks, ice to cool down, muscle pain-relief cream, and body butter for chafing. I was rehearsing what I was going to say once she arrived. I was planning on being positive, firm and direct with her, providing her facts of where she was in the race, her placement, and what she had left. I was also prepared in the event she was not doing well. All of this we had planned and rehearsed ahead of the race, but I still kept a small note in my pocket to make sure I would not forget anything.

I could see Kelsey running towards the aid-station tent for about 10-15 seconds before she entered. She arrived with a big smile on her face and could not wait to tell me a story about a baby cow looking like her dog Ralph. My plan to be serious and direct faced its first challenge as I could not help myself from giggling at her story and her demeanour. We were definitely experiencing some end-of-race loopiness and attempts to delay. I snapped back into the plan and gave her the placement information: she was currently in 28th place for women and ahead of her time from last year by about 3 hours. Her reply: an excited “Oh wow! Really?”. I gave her some information that the woman who left the aid station before her was heard saying that she felt she had no legs left. Kelsey’s reply: a very concerned “oh no!” and later on, a very loopy “I have TWO legs”. I firmly reminded (while stifling some of my own giggles) her that this was not the time to feel bad for her competitors, that it was time to take advantage and leave them in her dust. And once we had replaced her water and fuel, applied some muscle cream and body butter, and she had eaten a freezy-pop along with some pretzels and crackers, it was time for the pre-exit pep talk. I looked Kelsey straight in the eyes and asked her very firmly, “Kelsey Hogan, what is your superpower?”. And what Kelsey did next will forever be the best representation of her character, strength and superpower. Kelsey threw her arms into the air, leaned her head back and exclaimed, “I LOVE RUNNING!”. I could not help but burst into laughter. I gathered myself and I told her that she is by far the toughest runner out there and that she could still pass plenty of runners before she finished the race. She had 12 kms to the next aid-station where her dad would be waiting for her. I directed her to the exit, where she met with the rest of the crew who followed her out to the route leading her back into the mountains, still trying to tell her baby cow story.

Off we went to the next, and last aid station. This was one of the segments where the drive to the next aid-station was shorter than the race route, so even though Kelsey had “only” 12kms to run to us, we would finally have enough time to settle into an aid station and have some hot food. During this time, we kept paying attention to the live-tracking and suddenly, the potential for Kelsey to finish the race under 30 hours seemed like a real possibility. She had left Trient with an estimated finish time of 31.5 hours, but with each timing checkpoint, she was shaving off significant minutes and picking off runners ahead of her. While the primary goal was to beat last years’ time, the next significant goal was that 30-hour mark. It would also mean (selfishly) that we would be able to get a full night’s sleep in our beds with a sub-30-hour finish!

In some excitement amongst the crew, we began to discuss the appropriate information for her dad Noel to share with her at the last crewed aid station. She was still feeling good physically and doing ok mentally, so we decided that Noel would let her know that 30 hours was within her reach, that she would need to push even more, but it was possible. There’s a delicate balance between pushing and being safe with a runner with still 20km and about 3-4 hours left in a race (now back in the darkness of the night). We also knew that fueling for this last push was imperative. So, a meal of french fries and coca-cola were on the menu to provide enough energy for that final push.

The aid-station in Vallorcine, France is set up in the centre of the small village at the foot of a hill clearing where you can watch racers make the descent into town before running another kilometer or so around town and into the aid-station. We found ourselves at the “imminent” stage staring up the hill to see if we could spot Kelsey’s teal coloured t-shirt amongst other runners and local hikers. We made a couple of mistakes before we finally saw her flying down the hill with her arms outstretched and responding to our crew calls. In the aid-station with Noel, she enjoyed her pub fare and asked a couple of times how much farther she had to go. She looked both tired and energized – if that’s possible. She certainly looked better physically than most runners coming through this check-point – a fact we made sure to communicate with her. She left Vallorcine in 28th place for women and 183rd place overall and now 4 hours ahead of last years’ time. Sub-30 was very realistic now and Kelsey was determined. She had just over 100m left to climb. The final 10km would be all downhill – and after 166kms, downhills can be just as difficult, if not more, than the climbs. To say that Kelsey flew down those last 10km would be an understatement. She would later tell us post-race that she was having a tough time doing the pacing math in her head, so she decided to “just gun it”.

The crew made our way back to Chamonix in our final bus ride and walked the 20 minutes to our chalet to freshen up and drop our bags. All that was left was to meet Kelsey at the finish line and it looked like it would be before the clock turned to midnight. We purposefully took this time to lament our own fatigue and soreness to each other since it would be quite inappropriate to do so in Kelsey’s presence! And once we grabbed her finish line kit (fresh clothes, sandals, vomit bag), we made our way back to town centre, with a gelato pit-stop on the way.

The final kilometer of the race winds itself through the streets of Chamonix and there were plenty of race fans still lined up to greet the racers for the final push. Last year, Kelsey arrived around 4:30am so it had been very quiet. We were so pumped for her to experience this excitement this time around. Adam would situate himself at a spot with about 200m left to the finish line and with a direct route to the finish area where we would await Kelsey. Because we were not sure if we would be allowed on the finish side of the line, Kelsey wasn’t sure where we would be. But with some negotiating with security, we nestled into the finish area and got the cue from Adam that Kelsey was in fact “imminent”. The final straight-away of the race is only about 30m long so when Kelsey made the final turn towards us, she briefly looked at the crowd on the sides but quickly heard us straight ahead. When she saw us… I get emotional just thinking about. it.

Kelsey sprinted across the finish line in 29:32:24, safely under 30 hours, knocking off exactly 5 hours and 6 seconds from last years’ time. She passed 16 runners (3 women) in the final section to finish 25th in women and 167th overall out of about 2800 starters (1001 runners DNF’d). After some finish line pictures and making sure she was ok, we sent Kelsey and Adam off (by car) to their team chalet and made our way back to go to bed.

It is no surprise that the post-race plan is to rest, rest, rest. Kelsey also needed to slowly and carefully refuel. Once she gave us the “ok”, we headed to her chalet where there was a hot tub, champagne, laughs, and some happy tears. We had fun recounting our crew stories and reminding Kelsey of her funny stories.

I have worked in high-performance sport for over a decade now and have had the opportunity and privilege to work with some incredible human beings at some amazing events. This event sticks out for several reasons, and I take with me several lessons – some new and some reinforced:

First, the importance of preparation combined with adaptability. You can prepare, rehearse, simulate as much as possible (and you should), but to be truly prepared, you need to be adaptable. Second, communicating needs is imperative to make teamwork work. Running an ultra-marathon can happen without a crew, but it is definitely more challenging. The crew and the runner make up a team, and effective communication is integral. Because two of us were crewing for the first time, we asked a lot of questions that elicited a lot of productive conversations. Both Kelsey and crew members who had done this a few times benefitted from the barrage of questions as it prompted Kelsey to be clear and specific of what worked for her, and what did not. For example, it’s not helpful to tell an ultra-marathoner that they are “almost there” with 20km left to run. Communication also helped the crew work well together; I had only met Kelsey’s parents briefly last year and met Stef and Kaylee three days prior. In our crew discussions, we could always come back to, “what does Kelsey need”. Third, the mind truly is the keyholder of the body’s capabilities. Witnessing Kelsey and other elite runners in the aid and transition areas was a site to be seen. But then returning to the finish line Sunday afternoon to watch the final finishers, who had been on course for over 40 hours was spectacular. This leads into my fourth lesson. Ultra-marathons, much like other endurance sports, have a particular culture of community and supporting one another. There is comradery on the trails, runners suffer together and help each other out. In addition to the elite runners in the field, there are hundreds of others who are chasing personal goals and pushing their own limits. Races have traditions where the top finishers return to the finish line to meet the last finishers. Kelsey began her running journey for fun and enjoyment, and so the transition to competitive, professional running can feel a bit uncomfortable. I have a competitive personality, it’s in part why I love working in high-performance sport. And it’s why Kelsey wanted my help. There is no doubt satisfaction and pride in reaching one’s goals, but there’s also satisfaction and pride in being a part of something bigger. There is something significant and meaningful about pushing yourself to your own limits alongside of other humans. It is still difficult for me to understand why so many people would subject themselves to this sport. But I understand much better now having witnessed it myself.

As Kelsey often says: ultramarathons are a metaphor for life. We are each running our own, every day. I’m very grateful to have had the opportunity to share this experience with Kelsey and the rest of her crew. I’ll leave the running to her and look forward to crewing again soon.

Note from Kelsey: I’m so grateful for the support from my team for being part of this journey and for helping me get to the finish line at UTMB Mont-Blanc 2024. Thank you, Lori, for capturing the view from the crew — and for agreeing to come back to support my UTMB 2025 race!